In December last year I made an application to Arts Council England to write a collection of poetry, concerned in the main with the first convict settlement in Australia in 1788. It paid off; I got the grant, which just leaves the writing part. In the application I promised a blog to all and sundry, so here is an early glimpse of a few poems and an invitation to leave a comment on the work and the concept of re-telling that historic endeavour through imagined poetic voices.

I began writing the poems last May when I was in Sydney. I’d read Robert Hughes’s ‘The Fatal Shore’ and Tom Keneally’s ‘The Commonwealth of Thieves’. After Hughes one wonders what there is left to say on the subject but what Keneally does is spotlight the first two years, ‘the starvation years’ of the settlement and in particular, the uncertain lives of individual convicts, marines, officers and Aboriginal people who make up this absorbing drama that isn’t the story many believe it to be. But Keneally only goes as far as a historian dares and I wanted to see the characters actualised and more than anything, I needed to hear them. In some cases that was not difficult to do. The transported Cornish watch thief turned settlement farmer James Ruse soon began to boast of his achievement to me having, fed convicts and marines alike/ploughed out my life priced at two silver watches/at Bodmin Assizes.

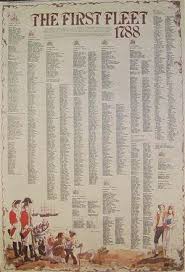

Initially I set out to tell the history of the first years of the settlement with quite a cast. I’d read every journal by officers and surgeons, noted their diet, the Aboriginal tribes encountered, the climate and the soil. A sequence of six was published in the last issue of Prole Journal which has been encouraging. What I have subsequently realised is that I also must go deeper rather than wider, to fewer characters about whom we know less or little. So, I strive to tell their mostly imagined stories through several rather than a dozen or more imagined voices. That way we may still get a picture of the wider experience in what was called New Holland. If I only achieve a sense of the personal experience of long ago extinguished voices that will be enough. Arts Council England have also funded a very patient mentor in poet and teacher Sarah Corbett who reminds me that the master I am writing for is poetry not history. This week sees the first instalment of Jimmy McGovern’s BBC television First Fleet drama Banished. Likewise he will no doubt do his job and serve his audience well. I only hope that his drama makes it more likely that people will want to read poetry concerned with 1788 and all that. Below, meet seventeen year old Jane Fitzgerald, a west country convict, seaman Jacob Nagle and Bennelong, the indigenous Australian who came to London when the first Governor returned.

Badlands

Jane Fitzgerald, Sydney Cove February 1788

Just the shine off them, the blackberries of home.

Bread dipped in butter, and chestnuts and eels.

My mouth is sore from fancying.

But I am not at sea now. I have my rations

without the pleasure of marines. They are ill-tempered.

Vermin won’t leave them be.

One who knew me on the Charlotte

struck another for two words to me.

He’s to be lashed for that. Won’t know his coat from his back.

After that I will go into the woods

lie all night in the dews with a highway robber.

A mutinous man.

We make free out here, of the land and the sea,

of each other. Marriage means nothing.

Seven or eight die each day.

There is talk of taking men to some island

weeks east. So red and rocky the earth

so fevered men behave.

They watch the lightning off the bay,

or look behind the camp up-river,

to China they say.

Healing

Jane Fitzgerald receives twenty five lashes for disobedience, March 1789.

I only talked with him. We like to talk with each other;

our corner in the shade. But Bloodworth the brick-master,

the henhouse sneak, has folk flogged now, easy as the Major.

William went to plead but mister Tench said

I have written the sentence down. William said,

count every second stroke Jane.

I couldn’t count after five. I pressed my face

into the tree like it was my mother’s skirts,

Bloodworth shouting damned bitch from the crowd.

I cried so I saw my daughters in Bristol.

The girls are taller, waist high to their father.

Their faces are clean, their hair shines, their mouths shut bravely tight.

When it stops we walk to my hut. My eldest holds my hand.

Women are separate from the men now.

We have our own fires and places.

But William is allowed, he nurses me.

His narrow fingers, soft as water make me sleep.

I dread the flies that’s all. Their footsteps along my wounds,

the shiver of their eggs.

William is no soldier. His uniform hangs off his shoulders,

he is young, taunted and ordered by all others.

But he brings me the healing leaves,

sets down his musket, reaches for me.

I will sew his torn sleeves.

Mercy

Seaman Jacob Nagle on board the Sirius, October 1788

Seamen are not convicts.

The way the continent has it

positons are ice islands, ebbing, slipping.

Convict, marine, Governor, seaman

are false landfalls

crawled upon, starved, whipped.

A native sits at the Governor’s table

while we are taken with scurvy

scudding the Horn in search of supplies.

Behind us every ghost lives a week

on five pounds of flour, four of pork

two pints of pease.

Whales are about us soaking the deck.

In the watch we have but thirteen left,

that with the carpenter’s crew.

Tied below the third lieutenant screams

Tip all nines and we’ll see

if she rises for a set of dammed rascals.

We saw land but three miles off.

The captain brought his charts on deck.

He overhauled them. We saw surf,

trees, hills there were, brush and woods.

A man died in sight of it.

Then it vanished. The Cape Flyaway.

I have my ring, my buckles.

If we reach Table Bay I’ll trade my seamanship,

return no more to Sydney Cove.

Bennelong in London

Bennelong after the death of his friend Yemmerawanne, Eltham May 1794

Father you stole me, tied me,

made my tongue turn like yours.

While our words mixed like colours Be-anga,

another man took my woman across the shore.

I paid you back with the spear, I had to.

Your forgiveness carried me across the black seas to here.

I have not met your King, I have met your Isabella

who has nursed me, tried to save my friend

Yemmerawanne. I made a ceremony alone for him.

I am invisible now, lazy as the moon.

There are men under bridges who cannot read the stars.

Some will come home on ships, some strangled where they are.

Once we were like long ago, when all

had been made, yet all was in darkness.

I shall be home when the Emu is in the sky.

Then I will leave my English clothes for good,

but keep a handkerchief.

Leave a comment